Precision Skills: Why Watchmakers are Choosing Decorative Engraving

Engraving is a skill that requires the creative eye of the artist and the steady hand of a surgeon. It has so much more to offer than simple personalisation, and watchmakers are increasingly leaning into this by offering decorative engraving on cases, dials and movements that tap into the trend for metier d’art flourishes. KaterinaPerez.com contributor, Rachael Taylor, explains more…

The Rare Handcrafts exhibition hosted by Patek Philippe in Geneva and London this spring was an insight into the world of the watchmaker. The focus of the showcase was not to celebrate those responsible for the construction of the watch’s internal world, as is so often the case with horology, but those who craft the external flourishes of some of its most decorative designs. This was a moment for the enamellers, the stone setters, the engravers.

The Patek Philippe exhibition is a sign of the times. The spotlight is shining brightly on metier d’art in the watch world right now, as maisons, including Louis Vuitton and Hermès, seek to awe collectors with complicated and rare goldsmithing techniques. It is a kickback against the ease of mass manufacturing, promoting the luxury of rarity. One of the metier d’art skills in high demand by watchmakers is engraving. While we might think of engraving as simply a way to add a personal message to the back of a watch case, the scope of the skilled engraver is vast. It can be used to add texture to metal, to set a map for enamellers, to introduce three-dimensional precious elements, and even bring colour when paired with new technologies.

Piaget has been experimenting with decorative engraving since the late 1950s, introducing its own house style called Palace Decor, which launched in 1961. This technique delivers the iconic vintage-style textured gold straps seen in the brand’s Limelight Gala collection. Each bracelet is hand carved to “transform it from ordinary to extraordinary,” as Jean-Bernard Forot, Head of Patrimony at Piaget, puts it. “It is a skill exclusive to Piaget,” says Forot. “It looks like guilloche, but the stripes are only horizontal, and don’t change.” He says the genesis of Palace Decor was Piaget’s decision in 1957 to work only in precious metals. “At this moment they started to celebrate the beauty of the gold in all its forms, and play with it,” he says. Forot has been unable to discover, as of yet, which individual craftsperson was responsible for inventing this style of engraving, but as soon as the first piece left the workshop, Palace Decor was a hit – and it continues to charm collectors today.

The way engravers work has changed over time, with craftspeople now aided by microscopes and lasers. Yet many still prefer to work with the traditional graver cutting tools and bowl vice. Such hand skills take years of dedication to master, and it is this type of engraving that watch collectors find intoxicating. “I think the more we live in a digital world, the more some people enjoy things that are made by hand,” says Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, President of Chopard.

When Chopard wanted to introduce fleurisanne to its collections, the brand had to learn how to create it in house

The brand has been experimenting with a very old style of engraving known as fleurisanne. It calls on the engraver to create elaborate scrolls and floral motifs by hand. It was popular up until the 19th century, but the craft has since died out. When Chopard wanted to introduce it to its collections, the brand had to learn how to create it in house. A Chopard artisan called Nathalie spent a year studying antique pocket watches with fleurisanne engraving and copying it. She then had to scale it down to fit the smaller proportions of today’s watches. Her steady hand worked precisely to tattoo the gold cases, dials, and movements of Chopard’s luxurious L.U.C. timepieces with her own reinvigorated brand of fleurisanne.

“There is no room for error,” says Pascal Béchu, Vice-President of Sales at watchmaker Arnold & Son, who holds a deep admiration for engravers. “Removing material is always possible, but adding more back is not an option.” Arnold & Son works with specialist engravers on decorative timepieces, such as its Luna Magna Year of the Dragon watch released in January to mark Chinese New Year. The dial is decorated with two hand-carved gold dragons. These mythical creatures emerged from the sketchbook of an Arnold & Son designer, who then transformed it into a 3D-printed model. That model was sent to an engraver, who replicated it by graving directly into solid gold.

Everything is done freehand, which leaves room for a certain interpretation and allows the craftsman to add his personal touch, and makes each piece slightly different, says Béchu. That said, the engraver must keep to precise proportions. And that is the whole art of the engraver: a work that is both artistic and precise.

Arnold & Son Luna Magna Red Gold Year Of The Dragon watch with onyx in 18k red gold and titanium

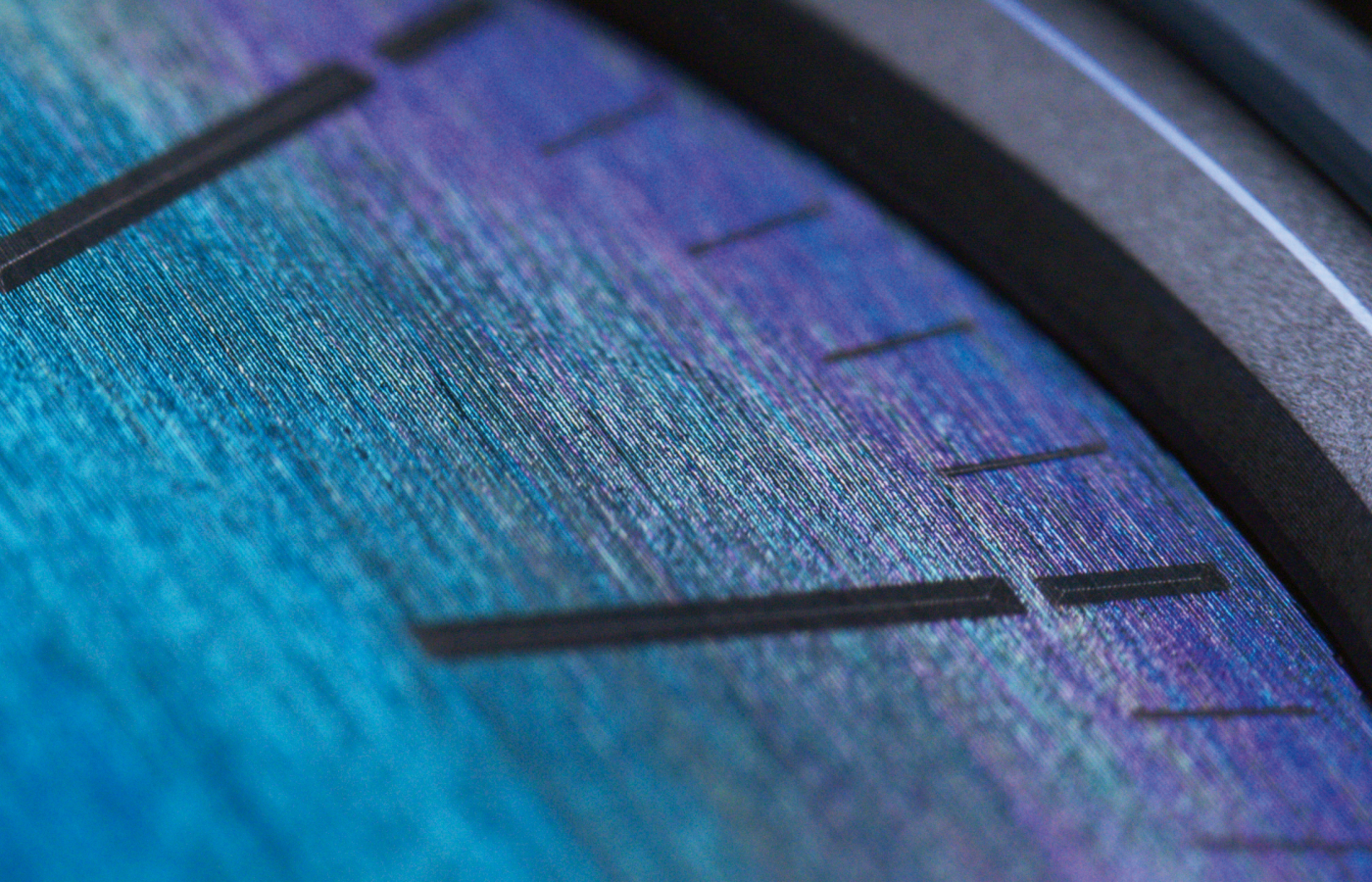

Engraving can also be used to introduce colour to a piece, often as an aid to the enamelling process. Designs will be graved into precious metal and then filled with colourful enamels. At Oris, watchmakers teamed with scientists at ETH Zürich University to develop a novel way to introduce colour through engraving. At the end of last year, the Swiss brand unveiled its ProPilot X Calibre 400 watch with a shimmering rainbow-hued dial that seemed to change colour as you move it. In fact, view it on a flat horizontal and the dial has no colour at all. This is because there is no pigmentation on the dial, just engravings that alter your perception. Each line has been carefully engraved into a titanium dial at a very specific depth to create optical interference known as biomimicry. The laser engravings disrupt light waves, destroying red waves while reflecting blue and green waves. This creates the illusion of colours.

So, the next time you think of engraving as just a simple way to personalise a watch, think again. This ancient artform – and its modern interpretations – has so much to offer to the modern-day watch collector, especially one with a penchant for rare and under-appreciated crafts.

WORDS

Rachael Taylor is a sought-after speaker, industry consultant and judge at prestigious jewellery competitions including the UK Jewellery Awards and The Goldsmiths’ Craft and Design Council Awards. She is also the author of two books on jewellery.

Related Articles

Latest Stories

Add articles and images to your favourites. Just

Century of Splendour:Louis Vuitton Awakened Hands, Awakened Minds Chapter II

Creative Director Francesca Amfitheatrof offers her unique interpretation of a pivotal period in France’s history, marked by the French Revolution, the Napoleonic era, and the rise of industrialism

Jewels Katerina Perez Loves

Continue Reading

Writing Adventures:Co-Authoring the Book

Paraiba: The Legacy of a Color

Brand Focus: Louis Vuitton

Jewellery Insights straight to your inbox