Lost Treasures: The Glorious Age of the Maharajas of Patiala

Indian royalty has always been synonymous with jewellery – not just for women but also men too, who loved to bedeck themselves lavishly in jewels. Such adornments were a way of establishing structure and hierarchy within a royal family. Many royal dynasties had their own trusted jewellers, but this did not stop them from admiring the creations of European jewellery brands. Unfortunately, battles on the world’s political map contributed to the dispersion of valuable jewels across time and space, with only a few, select pieces retaining their former grandeur and radiance. Let’s take a look at some of the historical jewels that are still with us today.

The Jewellery of Maharaja Bhupinder Singh

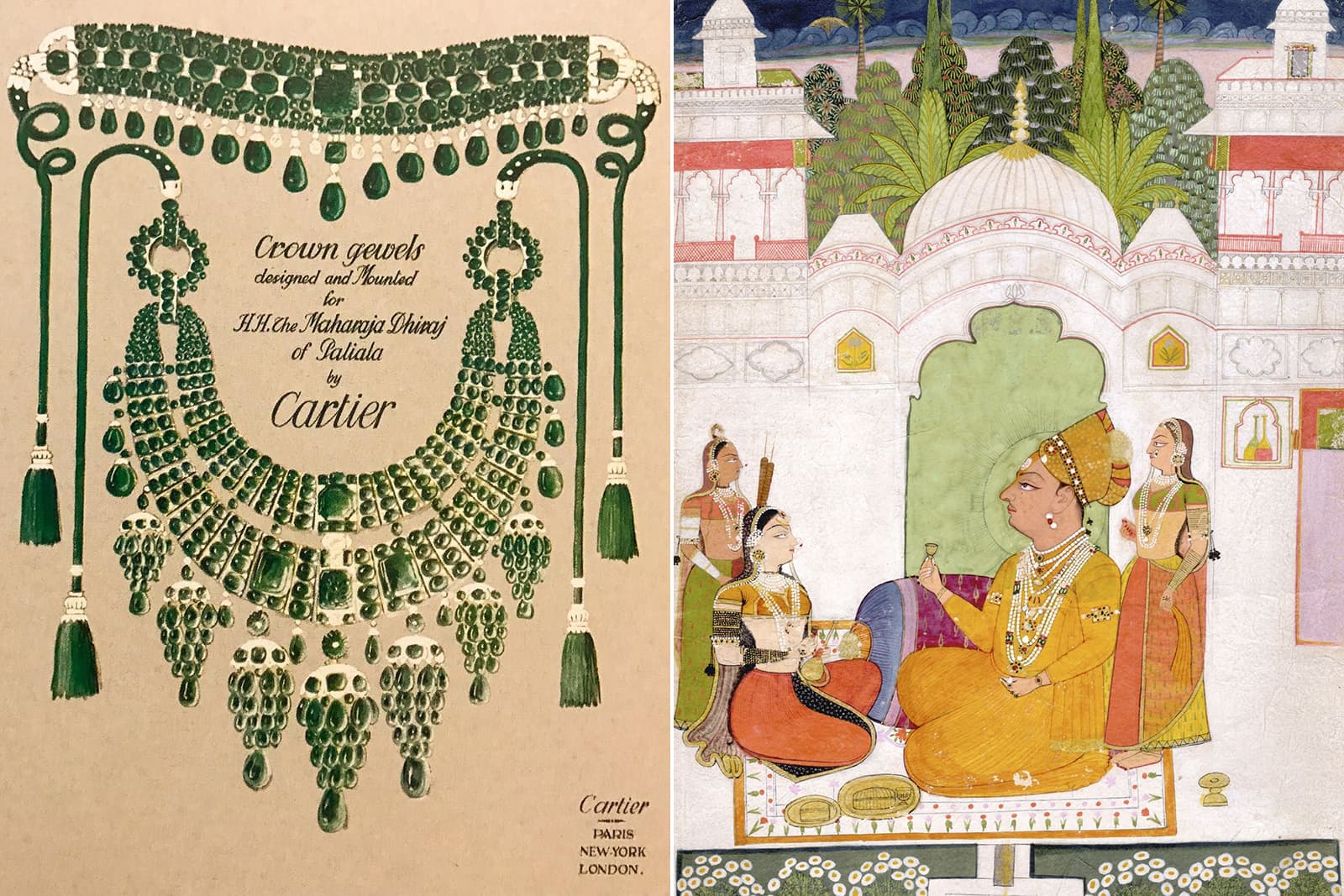

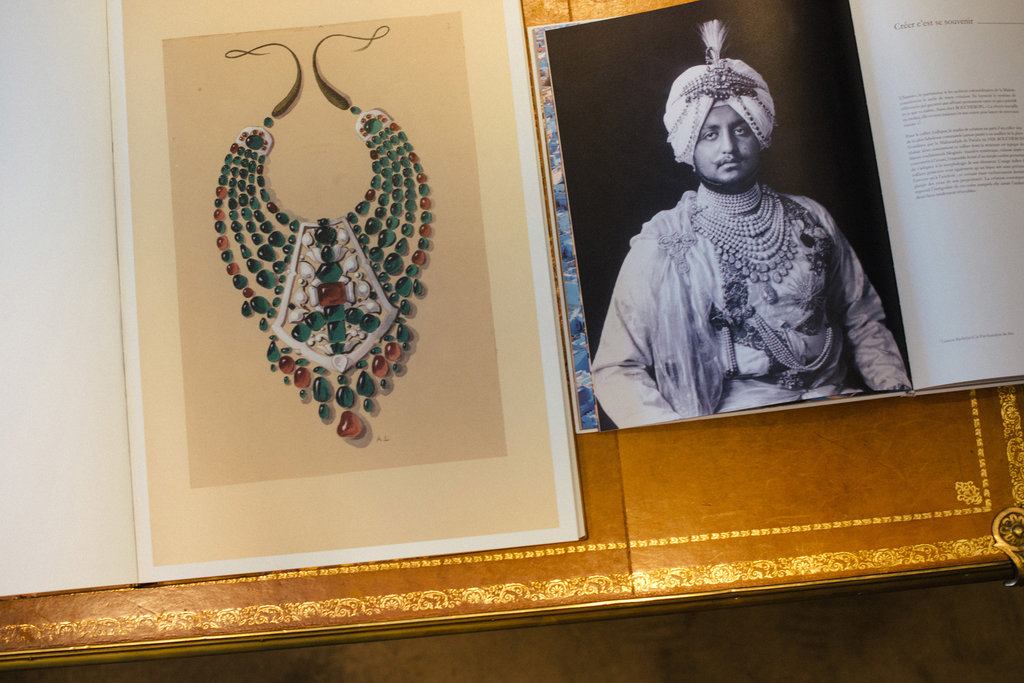

We begin with jewellery from the largest and most developed region of India: Patiala. In 1925, the 25-year-old Maharaja Bhupinder Singh travelled to Paris, bringing with him numerous boxes of precious stones: diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, pearls and rubies of the highest quality. The chief purpose of his visit was political, but he also decided to test the skills of Cartier’s jewellers during his stay. That same year, the brand was taking part in the International Exhibition of Contemporary Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris.

Cartier and the Maharajahs

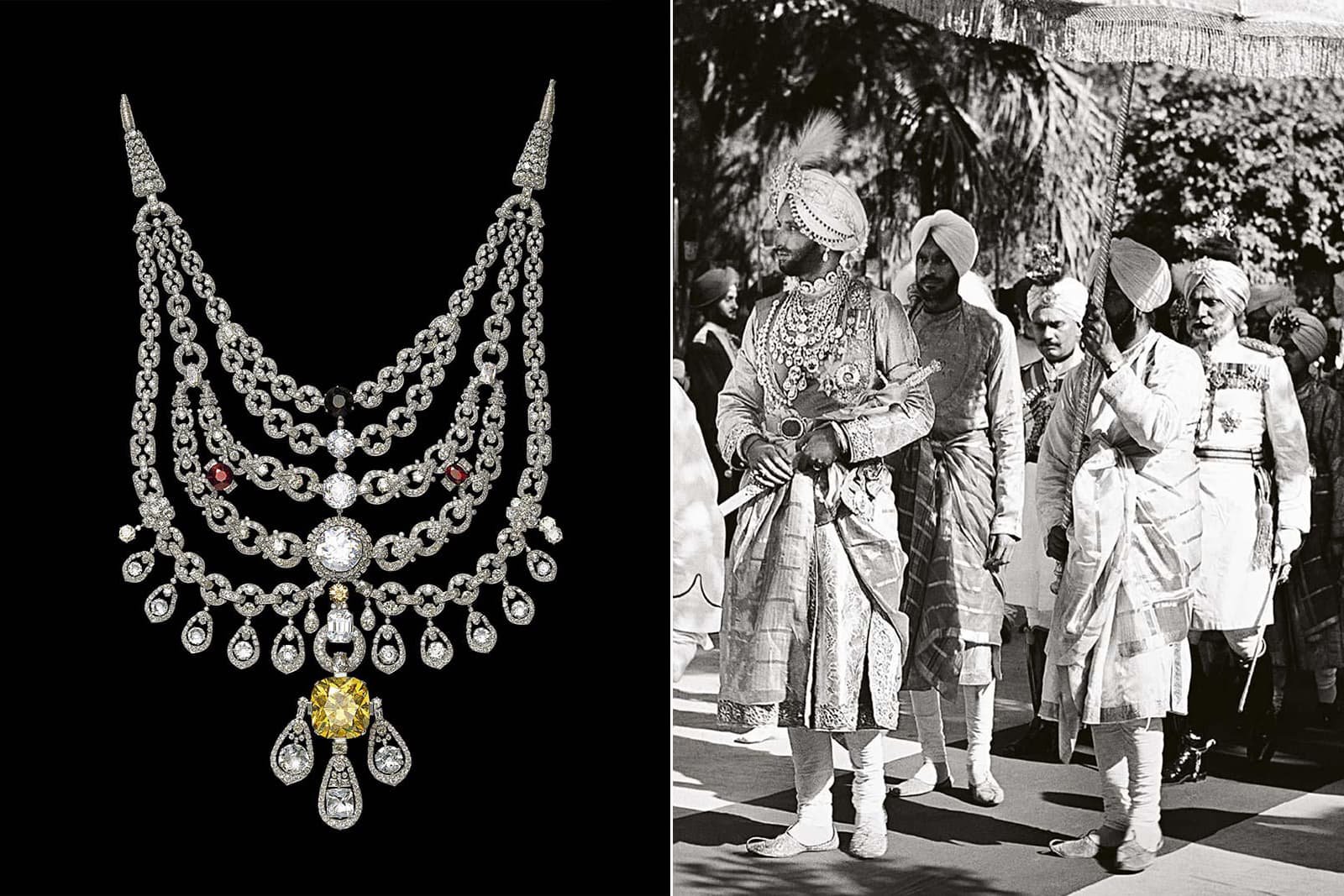

The Cartier display was one of the most prominent and, thanks to an order made by the Maharaja of Nawanagar, Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji, Cartier had managed to establish a name for itself among India’s rulers. A prototype of a ceremonial necklace with “only” 350 carats of diamonds so pleased Bhupinder Singh that he became a regular client of Cartier. In 1937, he asked them to take the “Tiger’s Eye” – an unusual cognac-coloured diamond – and design an Art Deco jewel for a turban. The Maharaja also donated 116 family Burmese rubies weighing over 170 carats. As it turned out, the necklace created by the Maison was not to stay with the Maharaja for long: by the early 1950s, it was returned to Cartier to be sold.

But let’s return, for a moment, to the vast expanse of Patiala. So as not to constrain the jewellers to certain precious materials as they fulfilled their royal commission, Maharaja Bhupinder Singh provided Cartier with 4,000 precious stones. The largest of these became part of the necklace, and the smallest ones were treated as payment for the work. As a result, three years later, the Maharaja received a necklace made with 2,930 diamonds weighing about 1,000 carats, including a superbly rare 234.65 yellow De Beers diamond.

Once the age of the Maharajas came to an end, all trace of this necklace was sadly lost until 1998, when it was found in London in an extremely damaged condition: the largest stones, including the central precious diamond, had disappeared. Of the original necklace, only five long chains of platinum, inlaid with diamonds, remained. The necklace is the most impressive jewel ever created by Cartier, so the Maison decided to restore it, replacing the lost stones with less-expensive alternatives.

The Art Deco Patiala ruby choker made by Cartier for Maharani Yagoda Devi, one of the Maharaja’s wives, in 1931

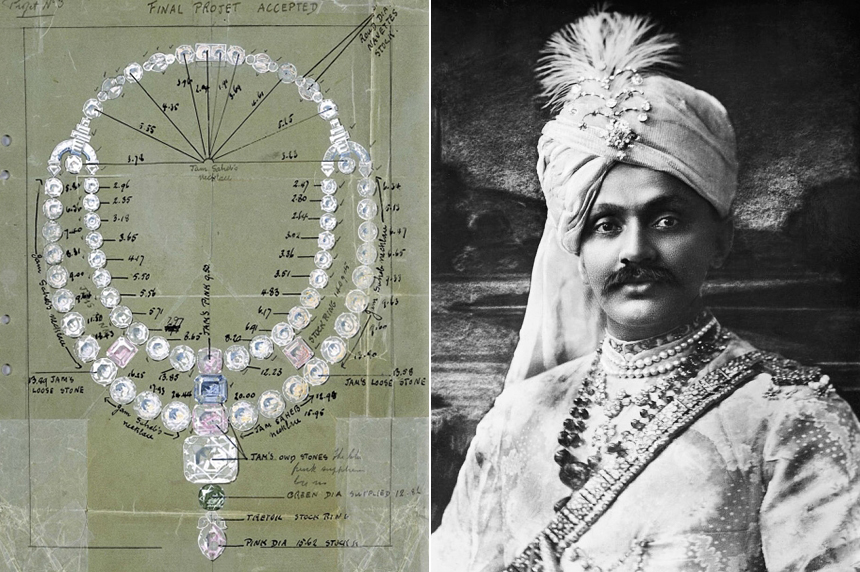

Maharaja Bhupinder Singh and the Boucheron Commission

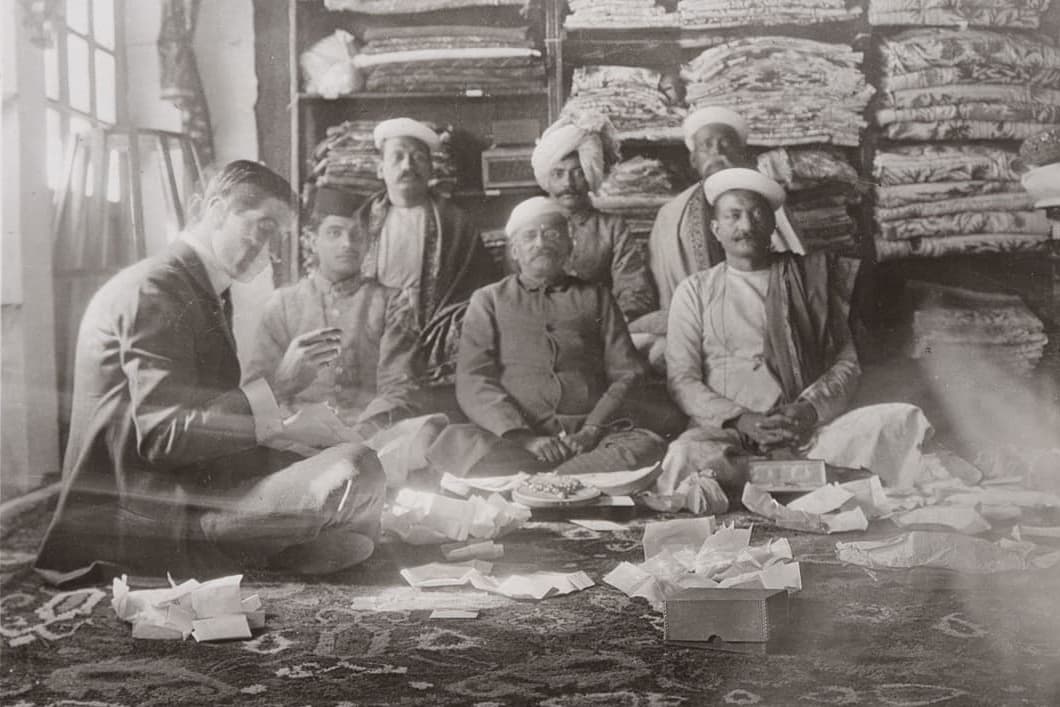

In 1928, Maharaja Bhupinder Singh knocked on the door of No. 26 Place Vendôme. Alain Boucheron recalls the visit: “The flamboyant Maharaja… He came to Boucheron in 1928, accompanied by a retinue of 40 servants in pink turbans, 20 female dancers and, most importantly, six boxes filled with 7,571 diamonds, 1,432 emeralds, sapphires, rubies and pearls of incomparable beauty.” From this wealth of minerals, Boucheron’s jewellers were requested to create a 149-piece collection. This order remains to this day the largest and most impressive ever placed on Place Vendôme.

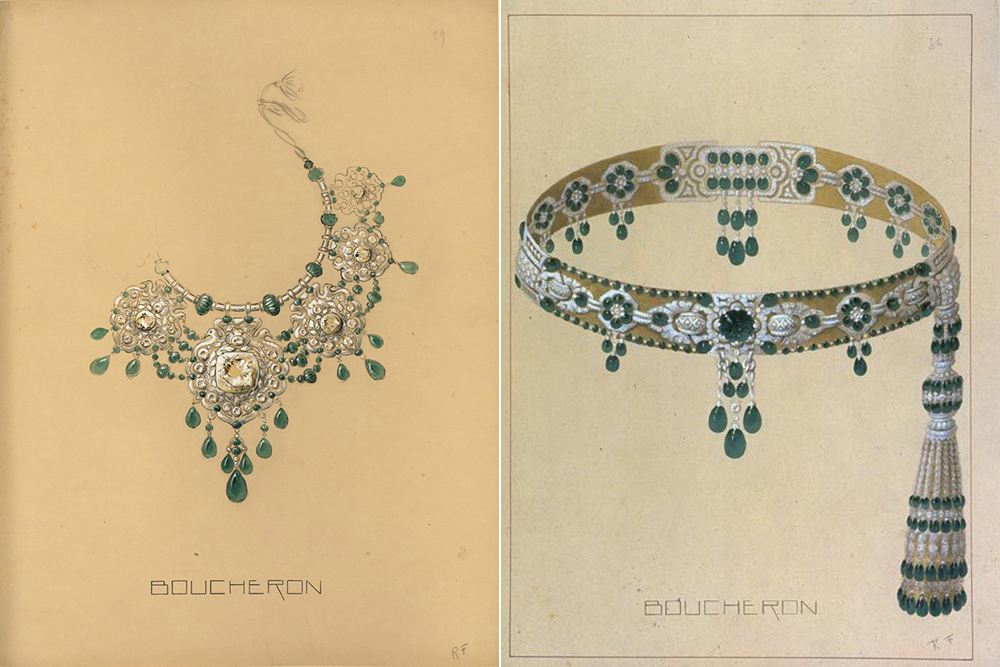

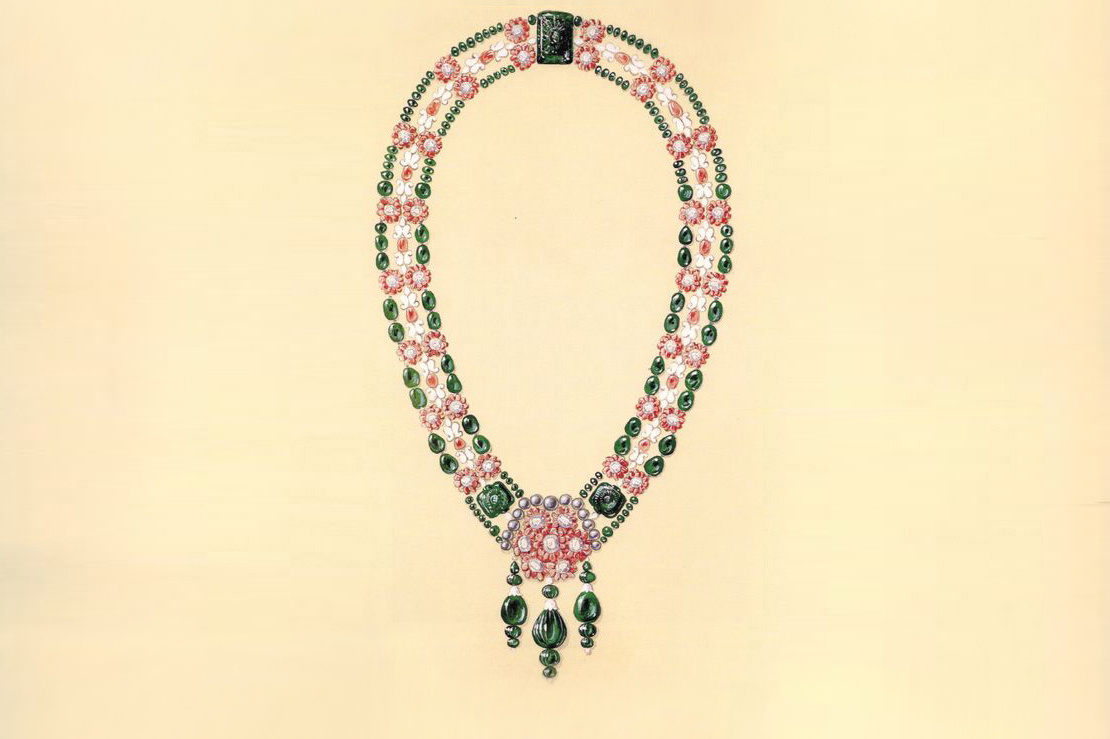

Unfortunately, what remains of the collection has disappeared into museums, personal collections and places unknown, but thanks to the magnificence of the order and the scrupulousness of the Boucheron archive, we have the opportunity to admire sketches and old photographs of these jewels.

Cartier Jewellery for Maharani Yagoda Devi

Maharaja Bhupinder Singh repeatedly returned to Cartier after that first magnificent creation – a piece that remained his favourite. But I would like to bring your attention to an order placed in the early 1930s. This time, Cartier was given a choice of rubies, pearls and diamonds that were to be turned into a necklace for Maharani Yagoda Devi, one of the Maharaja’s wives. This necklace and everything else from that moment in history, including the power of the royal family itself, have been lost. Part of the necklace was later discovered at a European auction house in the form of a bracelet. The find turned out to be the top tier of the choker, which has now been recreated by Cartier’s craftsmen.

It has to be said that this collaboration, and the creation of jewellery for Indian Maharajas, enriched Cartier’s aesthetic no less than the influence of European design and techniques. Carved emeralds, sapphires and rubies, found on a trip to India in 1911 and in the caskets of Maharaja Bhupinder Singh, inspired Jacques Cartier to create a daring gemstone combination that was subsequently labelled “Tutti Frutti”. The jeweller was also surprised to find that men were no less interested in jewellery than women and had more options, something which, of course, was reflected in Cartier’s selection. Epochs and rulers change, but jewellery still says something about the former greatness of its owners and commissioners.

WORDS