Rule-Breakers: The Most Iconic British Jewellers of the 1960s

The post-war explosion of counterculture led London to become the epicentre of fashion during the Swinging Sixties. Jewellery, too, would be forever changed as a new spirit of innovation and experimentation transformed what we considered adornment and gave birth to a clutch of iconic designers. Here are the most prolific names in British jewellery who make the 1960s such a fascinating and enduring time for fine jewellery…

In the mid-1950s, British jewellery design had become stagnant. World War II had put a kibosh on creativity, with boutique windows filled with rehashed Art Deco and Victorian designs rather than new creations. This wouldn’t last for too long, however. As the 1950s tipped into the 1960s, London became the epicentre of a new, creative jewellery scene teeming with up-and-coming designers ready to innovate. With a fresh take on what constituted a jewel, these designers would challenge the status quo with bold designs never seen before.

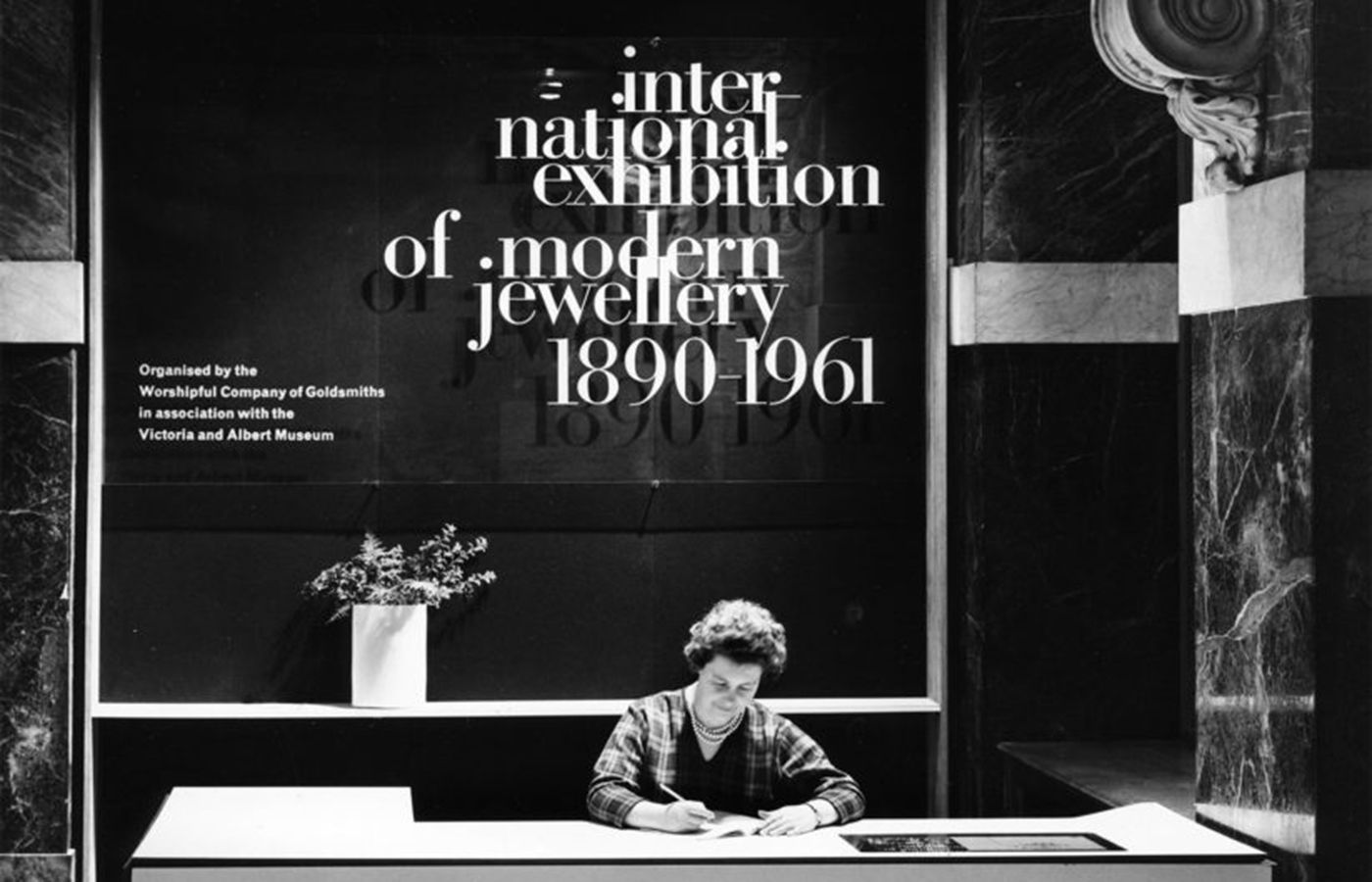

Goldsmiths’ Hall

A key moment in this time was the opening of the International Exhibition for Modern Jewellery at Goldsmiths’ Hall in London in 1961, curated by Graham Hughes. The exhibition brought together both artists, including Salvador Dali and Picasso, and jewellers, encouraging them to create provocative pieces of jewellery, and many credit this as really kickstarting the contemporary jewellery movement.

While the exhibition put such jewellery on the map, it reflected a movement that had already gathered some momentum in London in the 1960s. This was a time of innovation and experimentation and gave birth to trailblazing jewellers who would produce iconic designs. Here are our favourite designers from that seminal era.

Picasso Gold jewel

John Donald

Bored of the reproductions of Victorian and Art Deco jewellery, John Donald entered London’s jewellery scene in the early 1960s looking to disrupt. Being confined by what he could afford at the time, Donald created pieces with gold rods, which were less expensive than gold bars. This decision would lead to his signature geometric motif. Having designed for notable clients, including Queen Elizabeth II and the Queen Mother, Donald’s business really took off after he visited Kuwait in a bid to find new clients outside of the UK when the economy fell into trouble in 1971. It was a shrewd move, and he soon picked up many Kuwaiti clients with deep pockets. Donald is now retired but his designs regularly pop up on the auction market. In March, Lyon & Turnbull sold a topaz and diamond bracelet for £6000, and in 2020 Fellows Auctioneers sold eight of his pieces.

Andrew Grima

Considered one of the greatest jewellery designers of all time, Andrew Grima’s daring, uncompromising and abstract designs epitomise the rebellious jewellery of the 1960s, and still attract new fans today. In 2015, one of his rings set with a fancy greyish-blue 2.97ct diamond fetched £1.48 million at Bonhams. The Anglo-Italian jeweller opened his first boutique on London’s Jermyn Street in 1966 and provided an alternative to the conservative style of the era. He disregarded tradition, having not been formally trained, famously placing more value on the design of a piece than the gemstones set into it. Grima passed away in 2007 at 86 but is still regarded as one of the most influential jewellery designers of all time, with Marc Jacobs and Miuccia Prada being modern collectors of his pieces. His wife JoJo and daughter Francesca continue to keep his name alive, selling his original pieces and new jewels designed by Francesca under the Grima Jewellery brand.

David Thomas

David Thomas was one of the key jewellers of the new wave of 1960s jewellery. Featured in the historic Exhibition of Modern Jewellery in 1961, Thomas was celebrated for his three-dimensional textured gold designs set with unusual gemstones. The designer, who studied under Danish silversmith Goerg Jensen, considers jewellery making a form of high art, and he has redefined what people considered to be valuable by utilising unconventional gems in their natural states. Thomas met King Charles III while working for Collingwood of Conduit Street, and His Majesty – a fan – would later engineer the jeweller’s move to royal jewellery maker Garrard & Co. He would later design Princess Diana’s engagement ring, now worn by the Princess of Wales. The goldsmith’s relationship with the royal family continued to flourish, and he became the Crown Jeweller from 1991 to 2007. Thomas now shares his workshop in London’s Pimlico with his daughter Jessie Thomas, who runs her own jewellery brand.

Gerda Flöckinger

Born in Austria in 1927, Gerda Flöckinger moved to the UK in 1938. She went on to study at St. Martins School of Art, where she discovered a passion for jewellery and enamels. Graham Hughes featured her work at the International Exhibition of Jewellery in 1961, which showcased her Scandinavian-influenced, polished designs. She had established her brand by 1962, which repositioned jewellery as wearable art through her smooth surfaces juxtaposed with simple, hard edges, often opting for silver over gold. She was invited that same year to teach the country’s first experimental jewellery course at Hornsey School of Art, where she discovered her iconic fusing technique, where she used heat with precious metals to create new shapes, colours and textures and influenced a whole generation of jewellers.

Gillian Packard

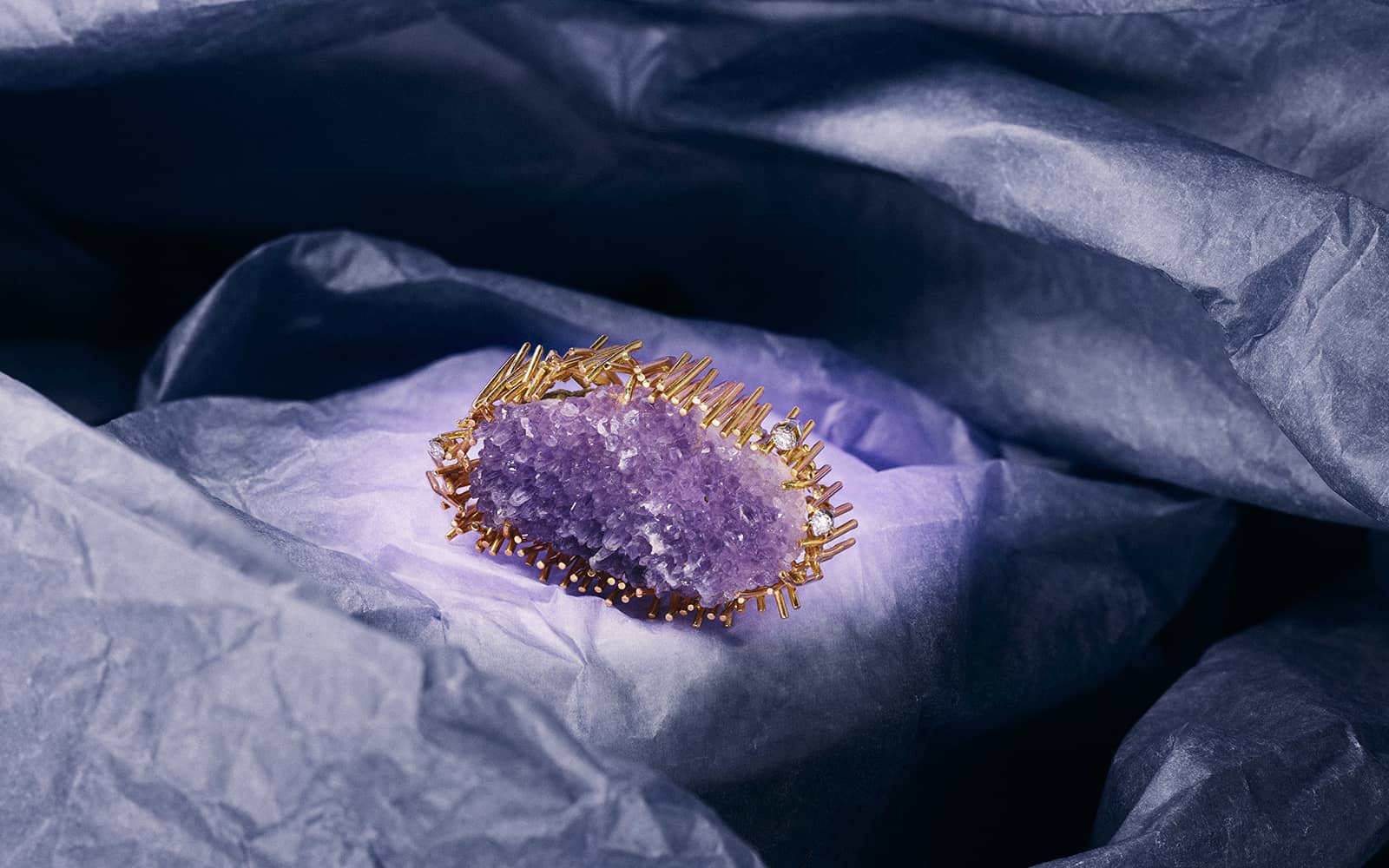

Another of Graham Hughes’ jewellers showcased at the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery is Newcastle-born Gillian Packard, who was one of the great contributors to the post-war jewellery scene. Her celestial designs explore texture, colour and geometry, and she only ever used diamonds as secondary stones in her pieces. Packard chose to distribute her works through shops and galleries rather than set up her own boutique, which led to her designs gaining fame throughout the UK. Packard was the first woman to become a Freeman of The Goldsmiths’ Company and was made chair of the British branch of the World Council for Applied Arts in 1969. During her career, she travelled the world promoting British craftsmanship.

1970s amethyst and gold brooch by Gillian Packard

George Weil

George Weil left Austria for London in 1939 on the last possible plane on the eve of World War II. Weil, who described himself as a sculptor first and jeweller second, would go on to study at St. Martins School of Art, but the rebellious creative was kicked out after just a few months. This didn’t slow down this true innovator, however. Weil tapped into his passion for sculpture while creating jewellery, and his bold, architectural style attracted the likes of Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra. During his career, Weil has been compared to Fabergé and designed for big houses, including Tiffany & Co. He stopped making jewellery and moved to Israel in 1989, where he continued to work as a successful sculptor.

Wendy Ramshaw

Wendy Ramshaw burst onto the scene after her flatpack paper jewellery, designed to be built by the wearer, was sold by the quintessential mod fashion designer, Mary Quant. Ramshaw’s flair for originality later led her to invent stacking rings, handing styling power over to clients. For this, she won a Design Council Award for Innovation in 1972. Ramshaw married fellow jewellery designer and sculptor David Watkins, and together they created large-scale sculptures and metalwork, including the Edinburgh Gates of Hyde Park, London. Her work has been exhibited in museums around the world, and at the time of her death in 2018, Ramshaw held both a CBE and OBE in recognition of her services to art.

Collection of ring stack from the artists estate of Wendy Ramshaw

Elizabeth Gage

Elizabeth Gage trained for six years as a goldsmith before launching her own brand. A turning point in her career was receiving her first big commission from Cartier in 1968. The designer finds inspiration in a wide range of sources, from the depths of the ocean to ancient bronzes. Her unorthodox and imaginative designs play out in gold, gemstones and vivid enamel. Gage claims to have coined the phrase ‘day-into-night’, a concept referring to jewellery that can easily be worn during the day as well as to glamorous evening events. Gage was awarded an MBE in 2017 and continues to oversee the workshop producing pieces under her name.

Jacqueline Mina

In the 1960s, the Royal College of Art did not accept women on its silversmithing course, which was Jacqueline Mina’s first choice, so she settled instead for its jewellery course and soon discovered an unexpected passion. Mina’s eyes were opened to what jewellery could be after visiting the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery. She began to experiment with texture and unusual gems and became fascinated with titanium, which she manipulates with heat to create bold colours and patterns within the metal. Now in her 80s, Mina continues to make all of her jewellery by hand using a mouth-operated blowtorch and is regularly featured at the world’s most prestigious museums and exhibitions.

A selection of golf jewels by Jacqueline Mina

Occasionally, pieces by these incredible jewellers find their way onto the auction scene and cause quite a flurry of excitement among collectors. True aficionados understand that 1960s British design is a milestone moment in the history of jewellery… we can still see its influence on designers and brands today. Here’s to a daring decade of style!

WORDS

Rachael Taylor is a sought-after speaker, industry consultant and judge at prestigious jewellery competitions including the UK Jewellery Awards and The Goldsmiths’ Craft and Design Council Awards. She is also the author of two books on jewellery.