Malachite: Renaissance of the Russian Gem

Malachite is an ornamental stone that has a unique appearance – its deep green colour interspersed with black streaks is entirely idiosyncratic and cannot be confused with any other mineral. Everywhere in the world, malachite is rightly considered a Russian gemstone thanks to the famed deposits in the Ural Mountains. They are even mentioned in the short story collection of Russian writer P.P. Bazhov: “The Malachite Box”. Despite the fact that malachite is primarily associated with the grandmothers jewellery, contemporary designers and brands found new uses for the unique stone, and one could say that malachite is experiencing something of a renaissance.

Throughout the 19th century, craftsmen worked with large pieces of malachite – fashioning them into home décor items and household utensils: jewellery boxes, vases, snuff boxes etc. There is even a malachite room in the State Hermitage Museum – the highest aristocracy used to indulge in these grand works of malachite ornamentation.

Piaget ‘Sunlight Journey’ cuff bracelet with malachite, emerald and diamonds in white gold

Working with the rough, jewellers began to admire unique patterning of malachite that, like lace, covered the work surface under the saw. However, guided primarily by the shapes they were making, the masters were unable to do justice to the beauty of the mineral and exploit all of the intricacies of the black – green pattern.

Bulgari ‘Serpenti’ secret watch with diamonds, malachite and rubellite in white gold

What about highlighting the beauty of the gemstone? Instead of working off its patterns, you drill them and carve flowers over them. What’s the point? This way you only spoil the beauty of the gemstone. – Danila, the Character from Bazhov’s Story ‘The Malachite Box’

Over time, the natural allure of malachite began to captivate jewellers: silver and gold brooches, as well as earrings and beads began to appear. Until recently, this was a phenomenon mainly confined to Russia. Nevertheless, over the last several years, famous houses from various countries around the world have begun to include malachite jewellery in their permanent collections: Cartier has minimalistic ‘Amulette de Cartier’ collection featuring pendants, ring, earrings and bracelet, Bulgari has ‘Diva’s Dream’ jewellery, Chopard has ‘Happy Hearts’, while Van Cleef & Arpels has the ‘Alhambra.’ However, it was Boucheron who have very skillfully incorporated malachite into their high jewellery collection – ‘Nature Triomphante’ as opposed to everday jewellery.

Boucheron ‘Nature Triomphante’ transformable brooch with malachite, Colombian emerald, emeralds, diamonds, mother-of-pearl and lacquer in white gold

The luxurious collection consists of three chapters, with the second being Boucheron ‘Surréaliste’. It included about six pieces that showcased malachite motif. Despite the fact that this mineral usually serves as an accompaniment to the main gems, in Boucheron it played a supporting role in only a couple of the pieces, the rest had a prominent representation of malachite. One of the most memorable pieces of jewellery – the ‘Papillon Chromatic’ necklace – was richly adorned with a flock of butterflies, the wings of which were carved from malachite. I was also impressed by the ‘Manchette Graphique’ cuff – embellished with geometric inlays and beads from this beautiful patterned stone.

Boucheron ‘Nature Triomphante’ cuff bracelet with malachite, onyx and diamonds in white gold

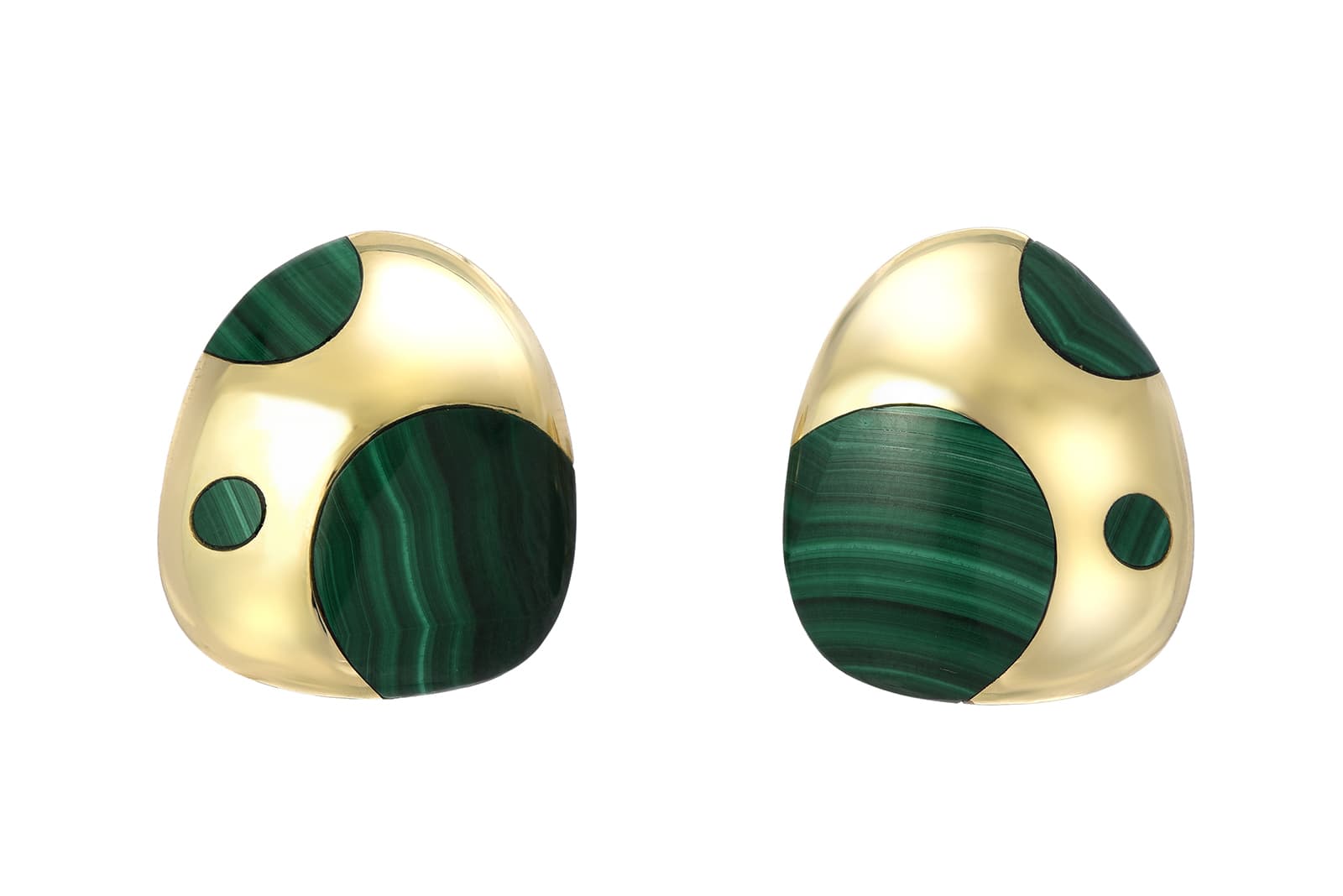

Thanks to the complex design crafted by mother nature herself – malachite is quite self-sufficient and works best in a design with very few additional decorative elements. That is why it is most often used as a part of fairly minimalist jewellery, such as the earrings, pendants and rings by Roberto Coin in their ‘Carnaby Street’ and ‘Sauvage Privé’ collection, or the VMAR hoop earrings and the Q-Ore bracelets and pendants – both from the ‘Mariana’ collection.

Malachite does not exceed a four on the Mohs scale – a measure of the mineral’s hardness. This means the stone is relatively soft and is ideal for carving. As an example, consider the work of art by the English contemporary artist Damien Hirst that depicts the cut off head of the Gorgon medusa – the entire object is made out of malachite. Pay particular attention to how highly detailed both the head and the snakes are! In the art of jewellery, examples are usually much less intricate, and it is more common to see various flat shapes cut out of the malachite: hearts from Chopard, quatrefoils from Van Cleef & Arpels, three-leaved flowers from Luca Carati are just three among many examples.

Damien Hirst Medusa Head malachite carving

Jewellery designers use malachite not only because of its attractive patterning, but also its spiritual associations. For example, Maral Melhem, founder of the VMAR brand, asserts that “malachite is a not just a beautiful green gemstone but it’s also important for protection as it absorbs negative energies whether from the atmosphere or our bodies. Malachite also has an ability to clear and activate the chakras as well as attunes to spiritual guidance.”

The gemstone I dedicated the article to is considered to be an inexpensive semi-precious stone, but nevertheless its potential is huge. Price and value are two different things, and now more and more jewellers are choosing their materials on a purely aesthetic basis, and not based on how they affect the price of the work after its completion.

WORDS

Katerina Perez is a jewellery insider, journalist and brand consultant with more than 15 years’ experience in the jewellery sector. Paris-based, Katerina has worked as a freelance journalist and content editor since 2011, writing articles for international publications. To share her jewellery knowledge and expertise, Katerina founded this website and launched her @katerina_perez Instagram in 2013.