James Taffin de Givenchy: Melanie Grant in Conversation with the Celebrated Jeweller

A few months ago, James Claude Taffin de Givenchy – the founder of Taffin which creates ultra-modern jewellery for collectors and aficionados wanting “to have something different”, visited London. During his stay, James spoke to a small number of invitees about his career and his views on jewellery design; in the form of a dialogue with Melanie Grant from The Economist. The conversation between the editor of a luxury publication and the jewellery designer seemed too interesting to be left behind closed doors, so I decided to share it with my readers.

James de Givenchy does not like publicity, so there is a possibility that you have not heard of Taffin jewellery yet; a jewellery company with a strong DNA rooted in New York. It was precisely the energy of the ‘big apple’ that attracted the young James, as he moved there from Beauvais – a town close to Paris. In New York, he studied graphic design at the Technological Institute of Fashion, then worked at Christie’s auction house, Verdura and Sotheby’s. Having established his own jewellery brand in 2011, he started transferring his love of graphic design to jewellery creations.

James Claude Taffin de Givenchy, founder of Taffin in his New York showroom. Image courtesy of Wall Street Journal

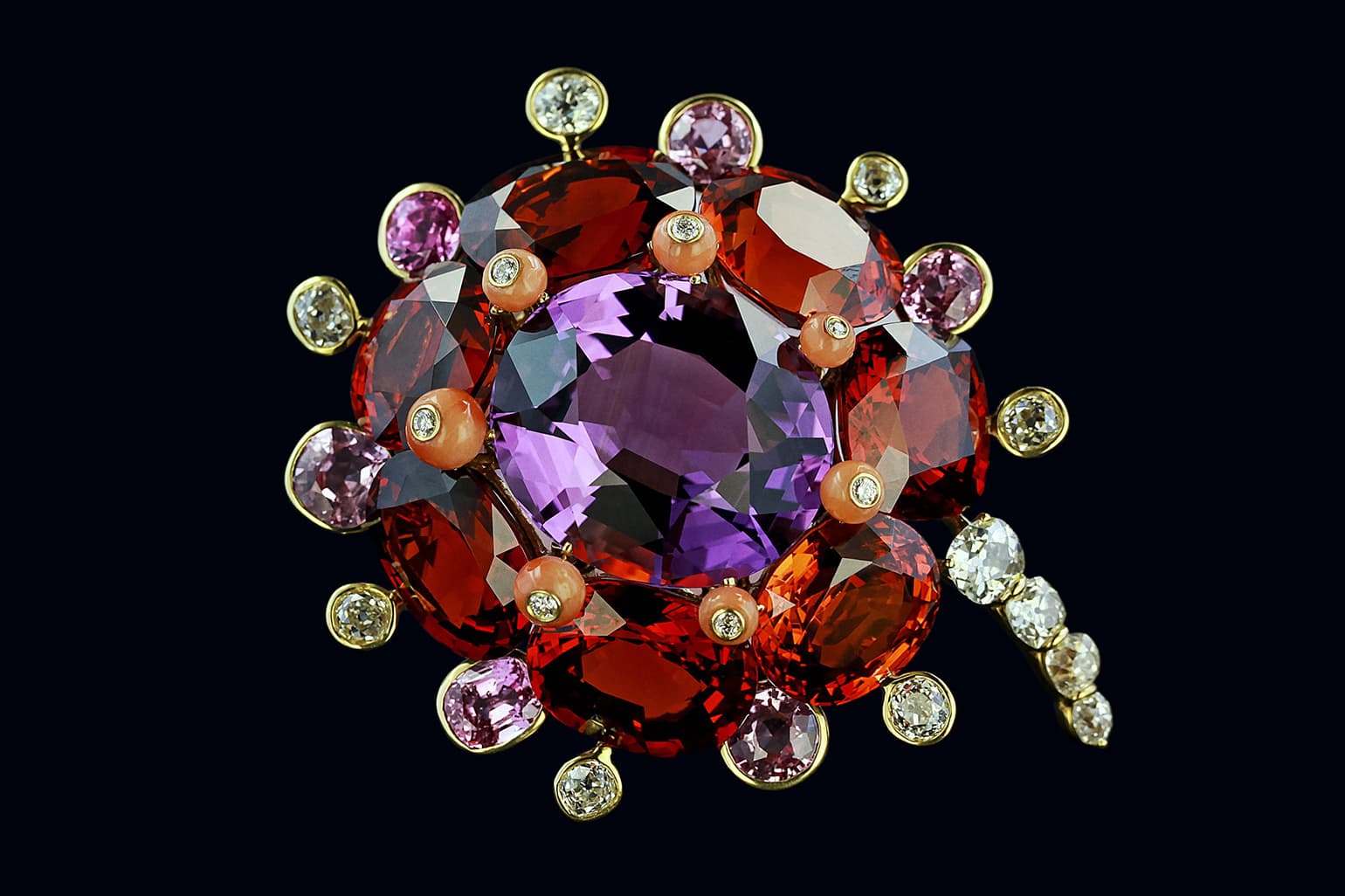

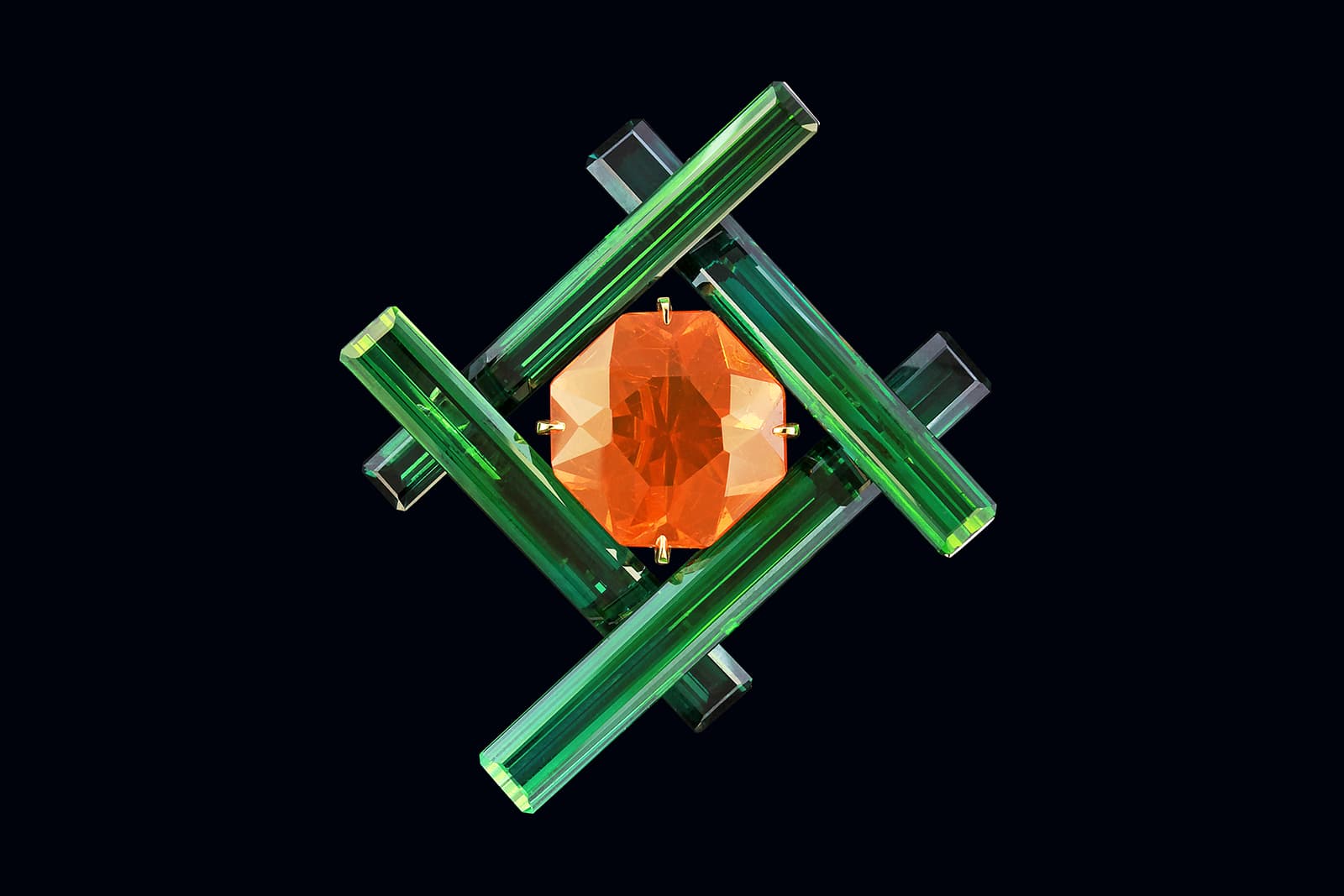

Taffin design never ceases to amaze with its bold combinations of coloured gemstones, innovative jewellery materials and chic laconicism in design. James often employs coloured ceramics – which has become one of his signatures – as well as unconventional gems, old mine and custom cut diamonds. As a rule, he removes all that is superfluous from the design until there is simply nothing more can be taken off, and the resulting minimalism is one of the things that makes Taffin jewellery instantly recognisable.

Melanie Grant: Tell us about the beginning of your jewellery journey?

James Claude Taffin de Givenchy: After graduation in 1986 there were no jobs, so I ended up going to Christie’s in Park Avenue and that’s where I discovered my love for gems. Once my uncle (famous fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy) walked in, and I wanted to impress him with the big diamonds – however, he pointed out one of the Verdura leaves that were made in the forties for Cole Porter. It was paved with zircons, bordered with a gold rim and azured in the back. He told me that if I wanted to get into jewellery, this is what I should look at. This was the trigger, and 6 years at Christie’s really opened my eyes to what jewellery is. Gradually, I realised that I wasn’t going to work in fashion or graphic design, I was in love with stones, and I was really interested in how jewellery is manufactured.

MG: What was the first piece of jewellery that you made?

JdG: It was a starfish, I was obsessed with the starfish by Boivin, so my first attempt at making jewellery was a mix between a Boivin style, and Verdura because I used only zircons and coloured pavé, as well as a touch of vermeil. I sold it to a client, and 10 years later it went up for an auction!

Taffin bracelet with coloured and colourless diamonds in rubber and platinum

MG: Is there anyone in particular who has affected you in terms of jewellery inspiration?

JdG: Verdura, Boivin, Belperron, as her work is very organic and she’s one of the greatest female jewellers. Cartier did some amazing work with Jean Toussant, they rarely have a star designer and she was a great influence.

MG: At some point, ceramic became your weapon of choice. When did you find it?

JdG: In 2006 Sotheby’s invited me to do a collection featuring colourless diamonds, although I usually work with coloured stones. I thought it was a great challenge, as these were some really fine stones and we were going to use steel, rubber, wood, and different materials that people didn’t expect. At the time, the only ceramic we could find was from China. Those were hard blocks of black and white, and the craftsmen were complaining about breaking every tool they had. But that was not going to stop me.

Taffin riviere necklace with tourmaline in silver and rose gold

MG: Then around 2009 you discovered an alternative?

JdG: Yes, at Baselworld they were selling a machine that creates hybrid ceramic which is a little softer and easier to work with. It was initially developed for watches, but I started experimenting with it. Now ceramic has become a signature of mine.

MG: Is there a part of your journey which you felt freed you creatively from what everyone else was doing? Obviously, the ceramic was a form of freedom, and you set a lot of stones upside down, which was odd at the time. Is there anything else you can think of?

JdG: Where you are young and lack of cash in the beginning, clients come and say “I want it this way” and you have to do it. But once you start being respected, people come to see what you do – whether it’s ceramic, wood, anything, and they say “here is a stone, do what you want.” This is what freedom is. Putting a collection together for a fair is freedom. Working on brooches is a freedom too as it doesn’t have to fit anything, you can be really creative as an artist.

MG: When you started, you were using fairly inexpensive stones – partly because of your restrictions with money, partly because you were doing something different. What kind did you start with?

JdG: Just about anything I could afford!

MG: With stones, there’s a lot of intrinsic value, which doesn’t help jewellery become closer to art in some ways. Do you think there’s too much emphasis now on stones in jewellery design?

JdG: The centrepiece is always about the stone you’re going to put in the middle, the intrinsic value of the gems we deal with is part of the jewellery industry, so I don’t think it’ll ever change. It has been a curse and an attraction for a piece of jewellery, but you see today a lot more people working with semi-precious gems, and I think it frees designers a lot.

James Claude Taffin de Givenchy, founder of Taffin in his New York showroom. Image courtesy of Architectural Digest

MG: You’re part of a well known fashion dynasty, do you think that helped you or hindered you in the world of jewellery?

JdG: I don’t think it’s hindered me. The De Givenchy name is great, but it is also a difficult name to live up to, especially in the sixties and seventies in France. As much as the world of fashion was there, there was also the revolution, and as a young person I was never anybody else other than my uncle’s nephew. So, France was difficult, and as much as I wanted to be a fashion designer, I was basically told to find something else. It wasn’t as liberating as America, where people would never say that – because of the success of my uncle, I would never be as good as him.

MG: Nevertheless, there were things that you have learnt from your uncle?

JdG: Definitely – never give up and keep up great work, as work itself is satisfying. I hate to think of success as anything because it’s not a ‘successful’ business – try to get a loan on my business! Banks are going to look at you and ask how many stores you are in. That’s not success, perseverance and hard work is going to give you what you want in life.

WORDS

Katerina Perez is a jewellery insider, journalist and brand consultant with more than 15 years’ experience in the jewellery sector. Paris-based, Katerina has worked as a freelance journalist and content editor since 2011, writing articles for international publications. To share her jewellery knowledge and expertise, Katerina founded this website and launched her @katerina_perez Instagram in 2013.