Who did the Cheapside Hoard jewels belong to?

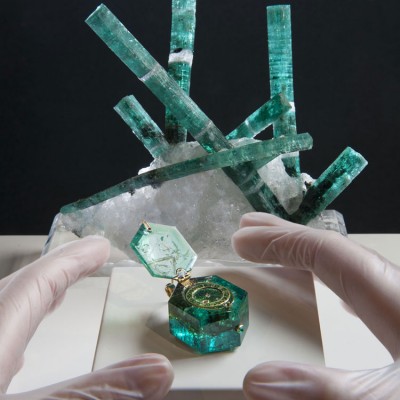

In October, the Museum of London opened an exhibition featuring the “greatest hoard” of treasures from the reign of Elizabeth I and the time of the Stuarts. There are around 500 exhibits, including gemstones, jewellery, perfume bottles and watches. Most interesting of all is the fact that they have ended up in a museum not thanks to a noble lady who decided to give her prized possessions away for safekeeping. Rather, they are now on display by pure chance after being discovered buried in the ground by construction workers in 1912.

How did the jewels end up there and whom did they belong to? Were they purposefully hidden by someone? If so, why did no one come back for them? I should think these are the questions which visitors of the exhibition will unwittingly ask themselves. The curator, Hazel Forsyth, set herself the task of finding out the answers to these questions by undertaking her own investigation.

The result was something of a success: they managed to determine the identity of 18 jewellers who rented out the property at 30-32 Cheapside in the City of London, the very address where this trove lay hidden for almost 300 years. It turns out that one of the tenants was the 17th century swindler Thomas Simpson. His counterfeit pieces were sold as if they were the real thing for sums that were immense for that time; sometimes he would sell them for as much as £8,000. It is unsurprising that two of his “precious” rubies, found on Cheapside, are in fact nothing other than dyed quartz crystals.

Who did the Cheapside Hoard jewels belong to?

Nonetheless, the presence of faked stones is not sufficient to prove that the chest of treasure was simply a trickster’s nest egg. There is a theory that the items could have belonged to an ordinary jeweller who was called up to serve in the English Civil War (1642-1651). There were no such things as safes at that time and so jewellers would simply hide their creations wherever they could. Cellars were probably the most reliable hiding places and it seems one on Cheapside served that very purpose since that is where these stones were found, lying in wait, as it were, for their master.

Indeed, when they were found and acquired by the museum, amongst the jewellery, watches and gemstones was a tiny seal engraved with the crest of William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford, the title bestowed on him in 1640. It was this detail which allowed experts to pinpoint the date of burial: at some point between 1640 and 1666.

Who did the Cheapside Hoard jewels belong to?

Another possible explanation is linked to the Great Fire of London in 1666. Tens of thousands of homes were consumed by the flames, but most of the cellars remained unscathed. It is likely that the owner of the jewels left them behind in the rush to save himself and couldn’t get back to them after.

Essentially it’s anyone’s guess. Despite the newest state-of-the-art technology and all the research that has been done, we will never be able to say with certainty how the Cheapside Hoard came to be there and who was responsible for burying it. Be that as it may, whoever it was deserves our thanks: without that person or Hazel Forsyth, we would not have this kind of insight into the past or as good an understanding of the intricacies of the craftsmanship practised by jewellers in the mid 17th century.

Photos are courtesy of Museum of London

WORDS

Katerina Perez is a jewellery insider, journalist and brand consultant with more than 15 years’ experience in the jewellery sector. Paris-based, Katerina has worked as a freelance journalist and content editor since 2011, writing articles for international publications. To share her jewellery knowledge and expertise, Katerina founded this website and launched her @katerina_perez Instagram in 2013.