Gem Room: Constantin Wild and His World of Enchanting Gemstones

When we buy jewellery, hardly any of us think about the person who cut the precious stones that adorn it. True, the basic principles of cutting are pretty much the same no matter what kind of gemstone it is, but in the hands of a craftsman the stone’s character and individuality are brought to the fore; it begins to scintillate with its own particular sparkle. My views are shared by Constantin Wild, the famous stonecutter from Idar-Oberstein, whom I got to know at Baselworld this year. The story of his family was incredibly interesting; in fact, stonecutting has now been in that family for over 450 years.

The name of Wild is one of the most widespread in Idar-Oberstein. Initially, the family included goldsmiths, gem merchants and stonecutters who were among the very first stonecutting artisans in this German town: the family crest is marked with the date 1557. Constantin’s family can be traced back as far as the birth of his great-grandfather Johann Nicol Wild in 1673. The family’s beginning was a classical one: a stonecutter married the daughter of a colleague. Their son Johannes, born in 1711, learned the trade of goldsmith. Known by the name of ‘Alter Gehännes’, he was one of the founders of the local goldsmiths’ guild. His son Johann Carl, known as ‘Gehännese Carl’, had a daughter, Anna Eva, who was widowed at the tender age of 28. Later she fell for the young goldsmith Johann Carl Werle, descended from minstrels from Strasbourg. She bore him a son in 1820 – but he married someone else. Illegitimate or not, Johann Carl Wild was Constantin Wild’s great-grandfather.

Constantin Wild

In 1845-46, Johann Carl made the remarkable journey to St. Petersburg, which at the time was the centre of the jewellery industry. After returning from his long stint abroad, he was given the nickname ‘Russ-Carl’, but he was not keen on it. He looked at the parish records, counted the number of ancestors who had been given the name Johann or Johannes since 1557, and gave himself the name Johann Carl Wild IX. Whilst successfully running his own jewellery business, Johann Carl Wild IX took up stonecutting, and in 1847 founded his own workshop, which is now, four generations later, run by Constantin.

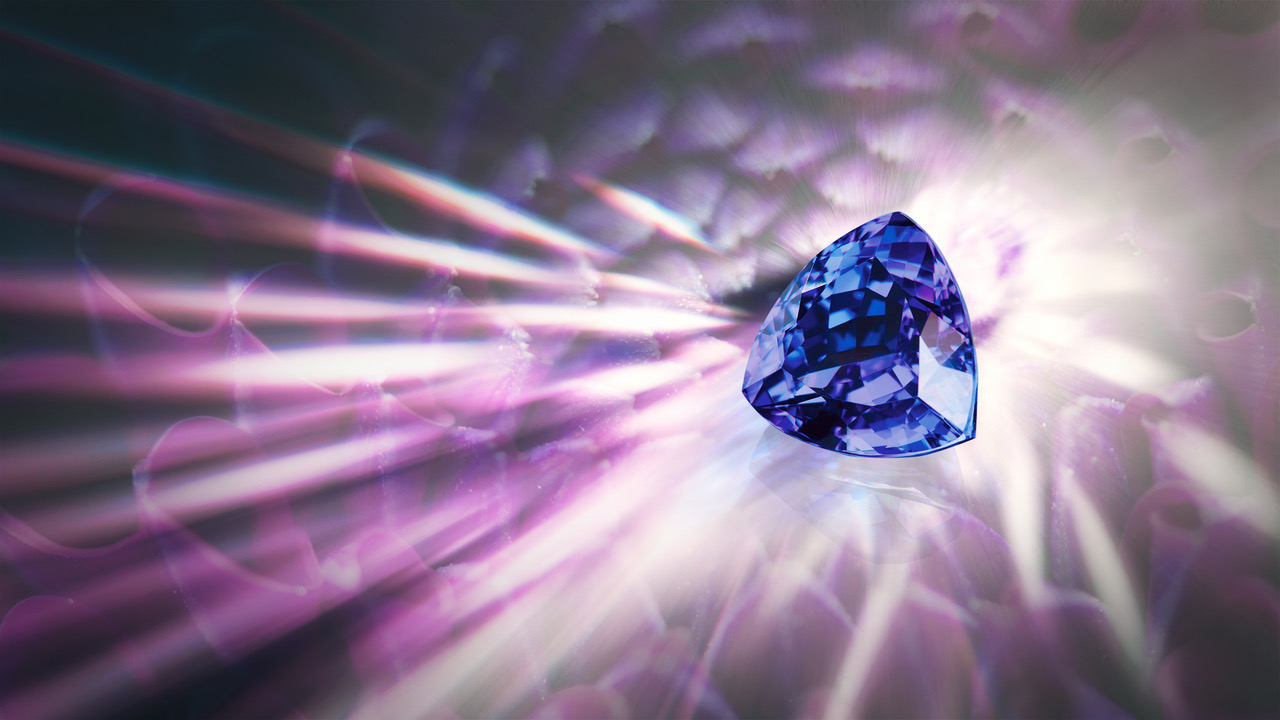

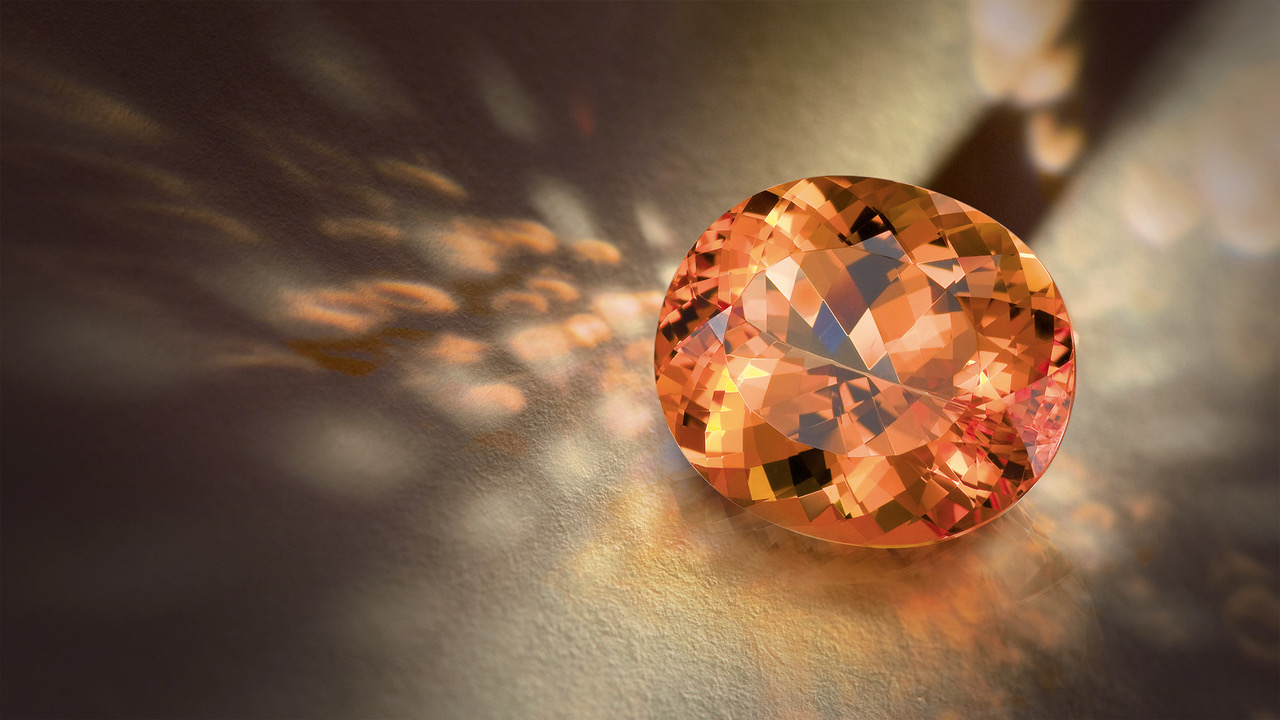

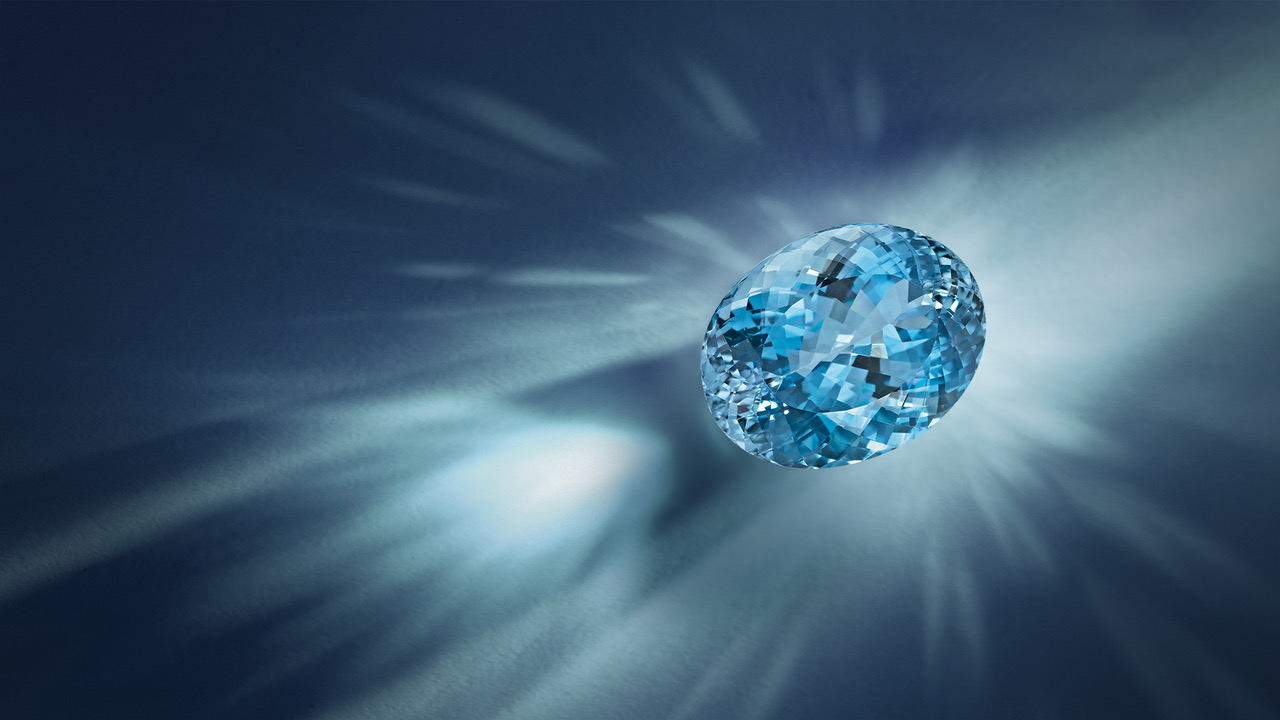

It seems that the most beautiful and rarest uncut stones on the planet fall into the hands of Constantin Wild with remarkable regularity. In Basel, I saw a unique sapphire with a rich orange hue, an enormous luscious rhodolite garnet, an entrancing imperial topaz and a truly magnificent paraiba tourmaline. I was struck not so much by Constantin’s ability to find the rarest of precious stones as by the sheer number he has managed to collect. Constantin is personally involved in this process, regularly visiting mines in Africa, Russia, Sri Lanka and many other countries. Incidentally, I discovered that he was one of the first to return to the demantoid garnet mines in the Urals where the ‘stone of the tsars’ was mined in the pre-revolution period. Now it is one of the most highly sought after gems, in part thanks to Constantin, who has been working with it since the end of the 1980s.

You can find Constantin Wild at exhibitions in Tucson, Hong Kong, Basel, or in his holy of holies Idar-Oberstein. In his spectacular ‘Gem Room’, with its rotating displays, the gaze of select clients can feast on an amazing spinel, a ruby with a radiant, deep crimson red colour, an orange flame-coloured garnet or a rare imperial topaz. Constantin’s precious stones are given pride of place, and the entrance of each ‘performer’ is staged with immaculate taste and attention to detail.

Constantin Wild

Stones that are at first sight unassuming can contain an astonishing array of multiple contrasting colours. Their appearance, colour and cut lend each of them a character of its own: feisty or peaceful, simple or subtle, sensual or joyous, flashy or humble – as diverse as the people who wear them. – Constantin Wild

The stonecutter calls his atelier in Idar-Oberstein his ‘treasure chamber’, a name that I think suits it perfectly. Its contents are renewed on an almost daily basis; those eager to become the owners of unique examples of rare sapphires, tourmalines, topazes, beryls and other gemstones travel to meet Constantin from all over the world. After leaving his hands, the precious stones have to meet a huge number of demands: a sleek radiance, sparks of light, ideal facets … perfection! At Basel, I was convinced that true artisans like Constantin Wild know their craft and are in no doubt about how to achieve excellence.

WORDS

Katerina Perez is a jewellery insider, journalist and brand consultant with more than 15 years’ experience in the jewellery sector. Paris-based, Katerina has worked as a freelance journalist and content editor since 2011, writing articles for international publications. To share her jewellery knowledge and expertise, Katerina founded this website and launched her @katerina_perez Instagram in 2013.